Reading papers - MT-DNN, MASS, UNILM, XLNet, RoBERTa, ALBERT,

During my previous studies, I examined research papers on various language models, including seq2seq, Transformer, and BERT (though I didn't write about BERT). My objective is gaining knowledge in the LLM field and also have an assignment requiring me to create a video presentation explaining the concepts I've learned in class to my peers. Previous posts are the result of the assignment. Therefore, this post will be too. :D

This post covers MT-DNN, MASS, UNILM, XLNet, RoBERTa and ALBERT. I won't describe the details of each model, but rather focus on the fundamental concepts (due to my schedule :p).

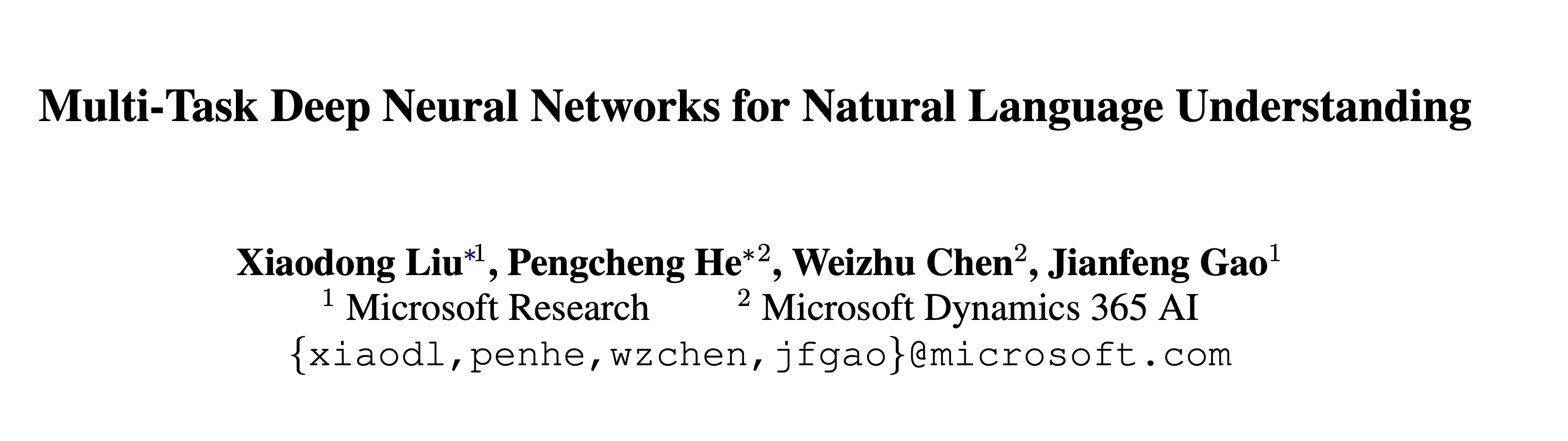

MT-DNN (Multi-Task Deep Neural Networks for natural language understanding)

In abstract, there is a key purpose of MT-DNN.

MT-DNN not only leverages large amounts of cross-task data, but also benefits from a regularization effect that leads to more general representations to help adapt to new tasks and domains.

And in the introduction, they explain the motivation behind MT-DNN, which is the basic principle of transfer learning.

Multi-Task Learning (MTL) is inspired by human learning activities where people often apply the knowledge learned from previous tasks to help learn a new task (Caruana, 1997; Zhang and Yang, 2017). For example, it is easier for a person who knows how to ski to learn skating than the one who does not.

They propose a diverse range of tasks to train the model:

However, I think the intricate details of these tasks are not essential for my current understanding. At this point, I'm focused on grasping the fundamental concepts rather than delving too deeply into the specifics.

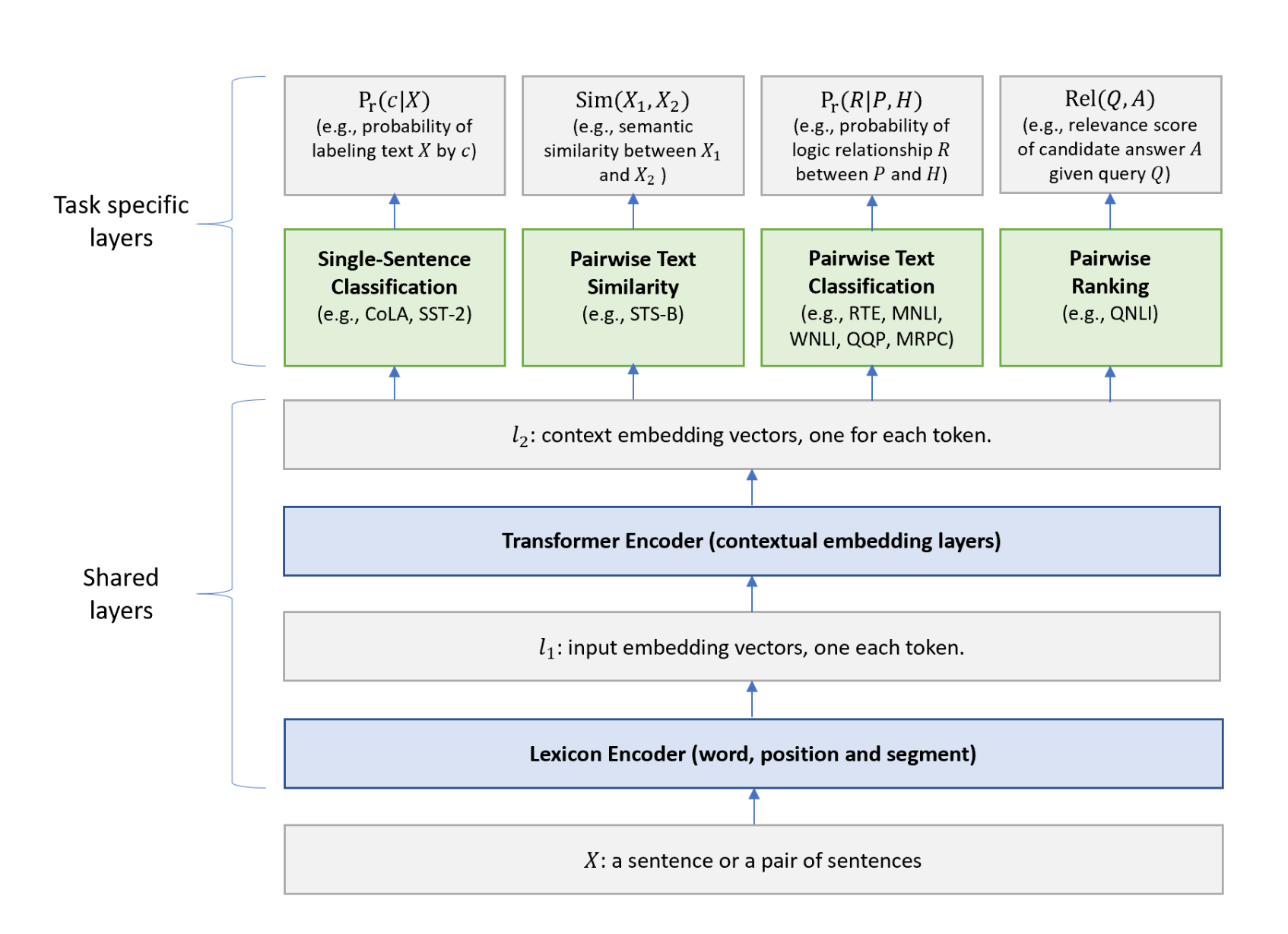

The benchmark is following:

MASS (MAsked Sequence to Sequence learning)

In abstract:

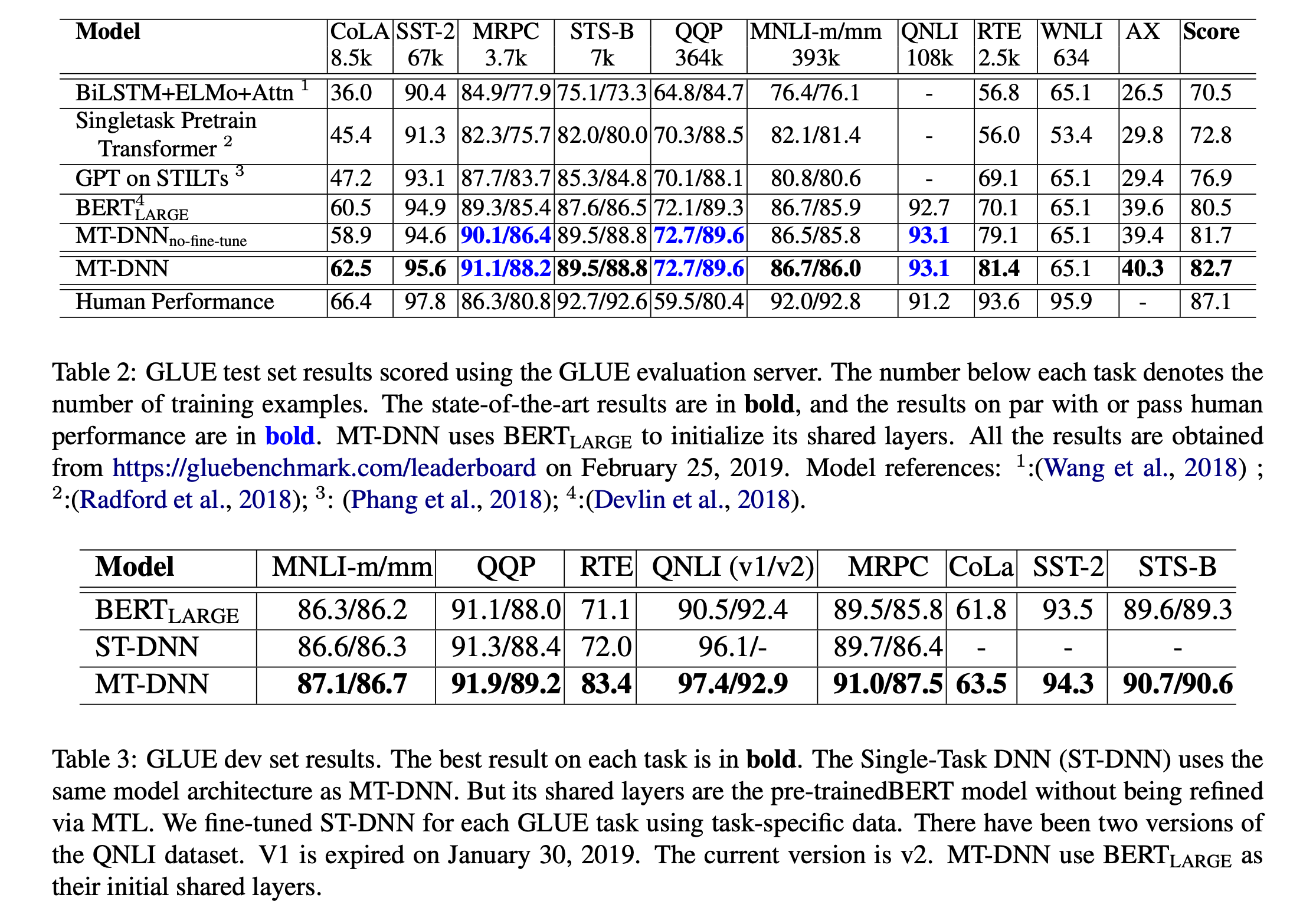

its encoder takes a sentence with randomly masked fragment (several consecutive tokens) as input, and its decoder tries to predict this masked fragment. In this way, MASS can jointly train the encoder and decoder to develop the capability of representation extraction and language modeling. In this paper, inspired by BERT, we propose a novel objective for pre-training: MAsked Sequence to Sequence learning (MASS) for language generation.

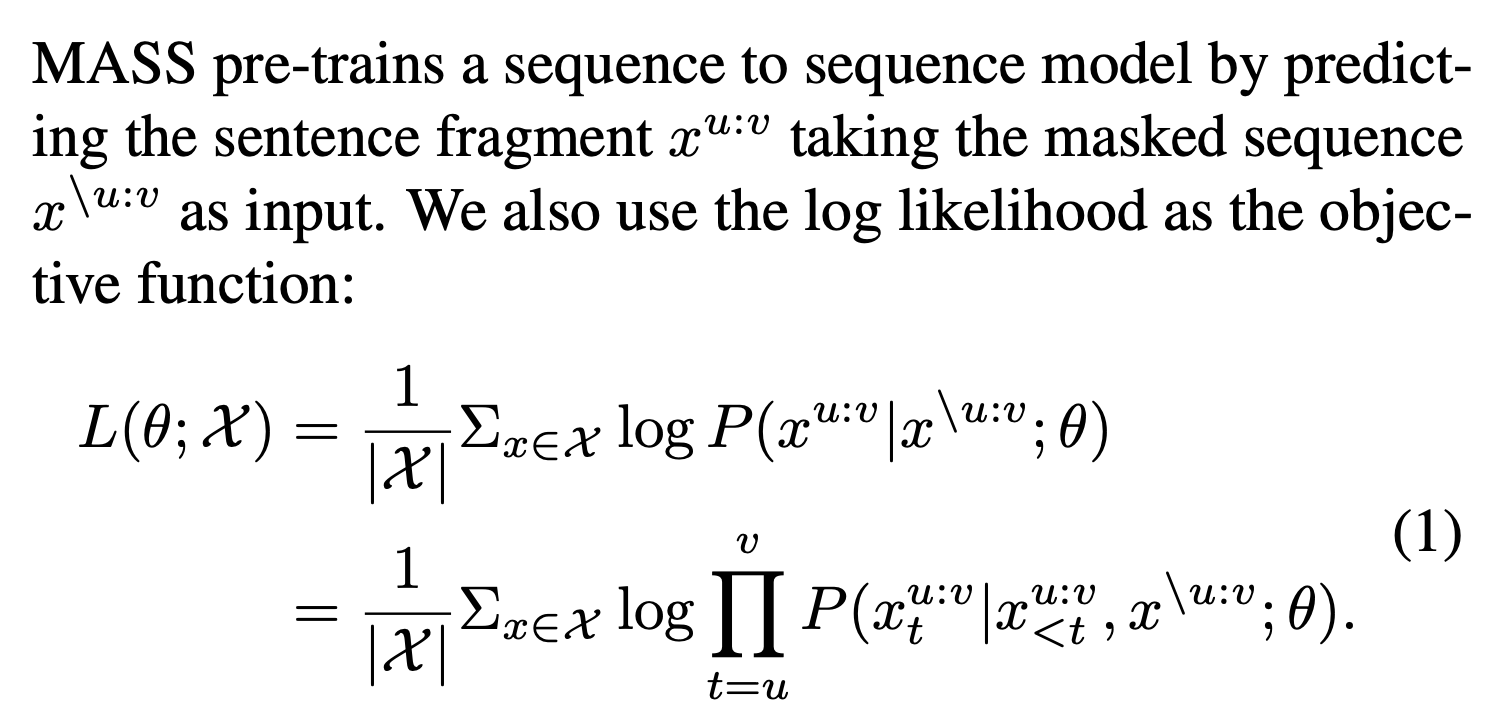

What does that mean? See the figure below:

MASS masks continuous sequences of tokens within the source sentence. Subsequently, the decoder predicts these masked tokens, generating the output seqeuntially, one token at a time.

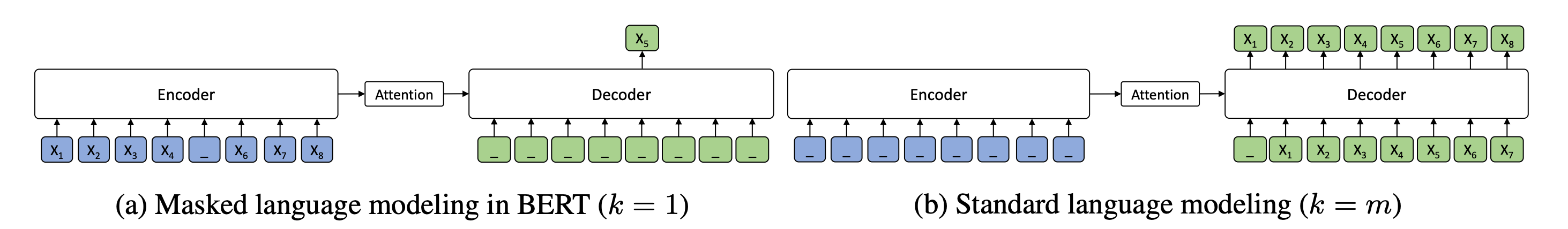

This provides a detailed mathematical formulation representing the loss function derived from the log-likelihood function:

Researchers assert that, under specific constraint condtions, MASS can effectively function as both BERT and GPT architectures.

However, MASS is the encoder-decoder framework to generate tokens and there is a cross-attention between the encoder and decoder. It is the fundamental difference from BERT (which is a single encoder architecture) and GPT (which is a single decoder architecture).

UNILM (UNIfied Language Model pre-training for natural language understanding and generation)

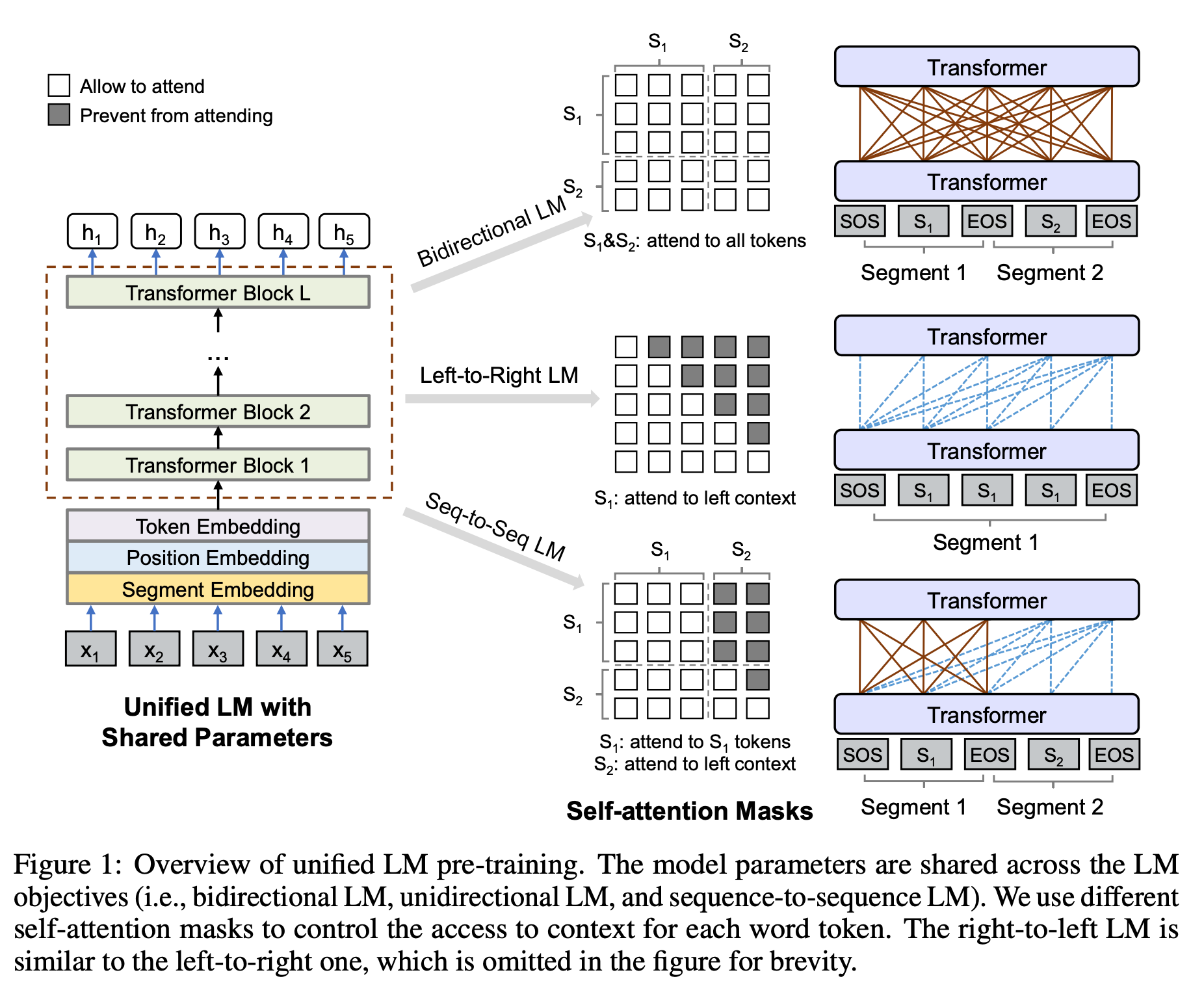

The authors describe UNILM's foundational architecture as a 'multi-layer Transformer network'.

However, upon examination of Figure 1, it appears identical to the encoder layer of a standard Transformer. (In fact, its architecture is precisely that of BERT Large.)

They implement a strategy that emulates language modeling techniques through the strategic manipulation of self-attention masks.

Specifically, within one training batch, 1/3 of the time we use the bidirectional LM objective, 1/3 of the time we employ the sequence-to-sequence LM objective, and both left-to-right and right-to-left LM objectives are sampled with rate of 1/6.

XLNet (XLNet: Generalized Autoregressive Pretraining for Language Understanding)

The name 'XLNet does not appear explicitly in the paper's title. However, the authors clarify the origin of this designation in the abstract.

XLNet integrates ideas from Transformer-XL, the state-of-the-art autoregressive model, into pretraining.

The nomenclature derives from their inspiration by Transformer-XL

What are the distinctive characteristics of this approach?

we propose XLNet, a generalized autoregressive pretraining method that (1) enables learning bidirectional contexts by maximizing the expected likelihood over all permutations of the factorization order and (2) overcomes the limitations of BERT thanks to its autoregressive formulation.

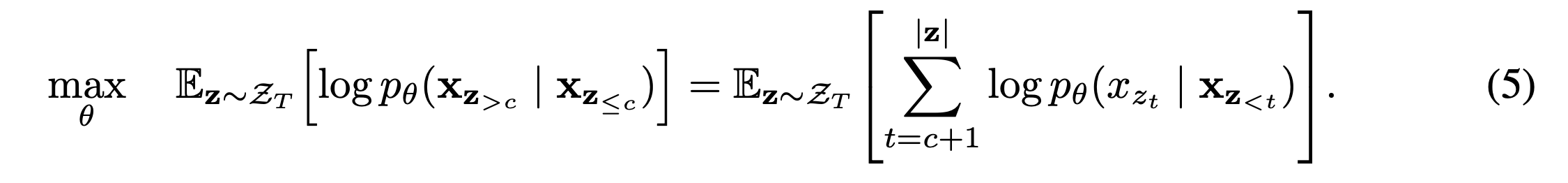

They propose an enhanced pre-training methodology that leverages permutations of token order. How exactly does this mechanism function?

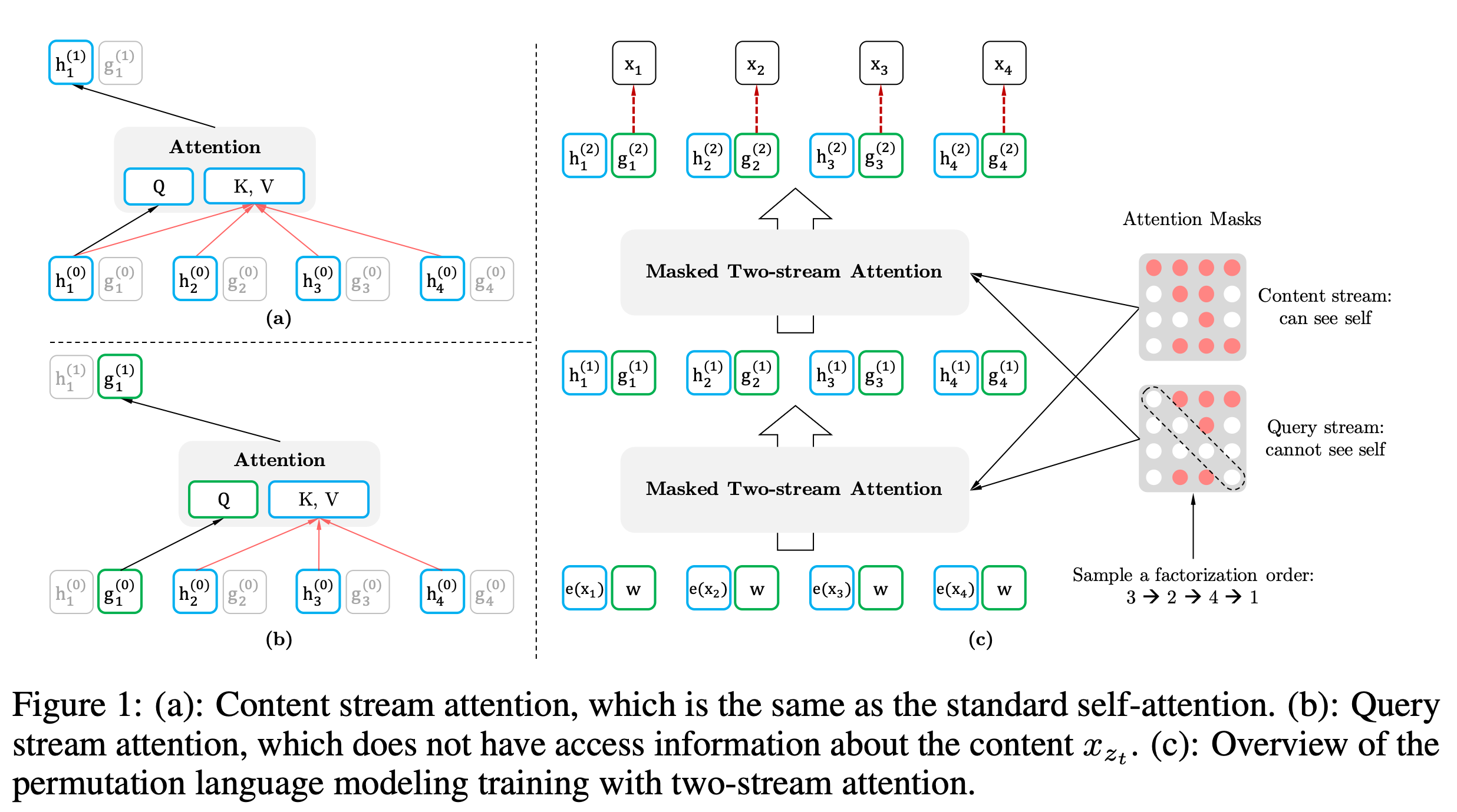

(a) shows the normal self-attention mechanism, and (b) shows the permutation self-attention what the researchers claim.

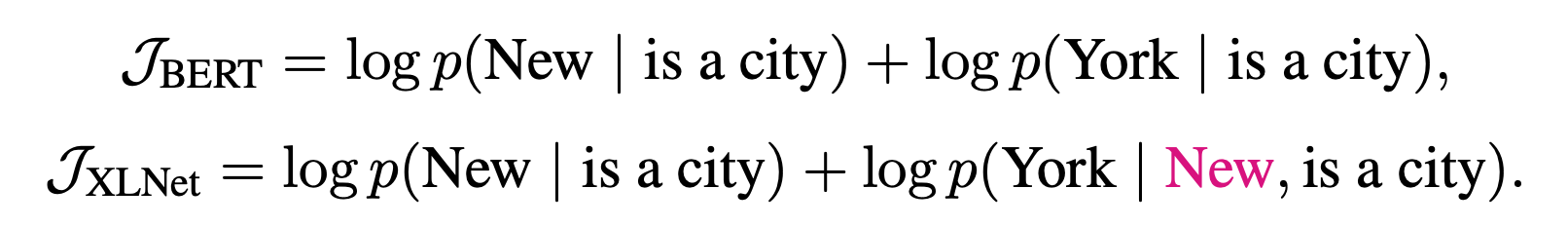

For instance, consider the sentence 'New York is a city' which would be masked as '[Mask] [Mask] is a city' in traditional pre-training. BERT's approach involves predicting 'New' and 'York' independently, calculating p(New | is a city) and p(York | is a city) separately. In contrast, XLNet employs a sequential prediction method: first calculating p(New | is a city), then p(York | New, is a city), thereby effectively capturing the relationship between 'New' and 'York'."

For those familiar with the inherent limitations of transformer architectures, particularly their substantial computational overhead, it comes as no surprise that XLNet inherits these same challenges. The authors were acutely aware of this computational burden.

While the permutation language modeling objective (3) has several benefits, it is a much more challenging optimization problem due to the permutation and causes slow convergence in preliminary experiments. To reduce the optimization difficulty, we choose to only predict the last tokens in a factorization order.

To mitigate this issue, they strategically implemented the permutation method on only a subset of the sequence, rather than applying it exhaustively.

In abstract:

hyperparameter choices have significant impact on the final results. We present a replication study of BERT pretraining (Devlin et al., 2019) that carefully measures the impact of many key hyperparameters and training data size.

So... the RoBERTa paper represents the better hyperparameter optimization. Our professor emphasized that despite its seemingly straightforward tuning methodology, this research emerged during a period saturated with numerous approaches and architectural innovations aimed at enhancing LLM performance. I concur with this assessment, as my review of several related papers reveals a predominant focus on architectural innovations.

From this perspective, the authors assert the following:

We find that BERT was significantly undertrained, and can match or exceed the performance of every model published after it.

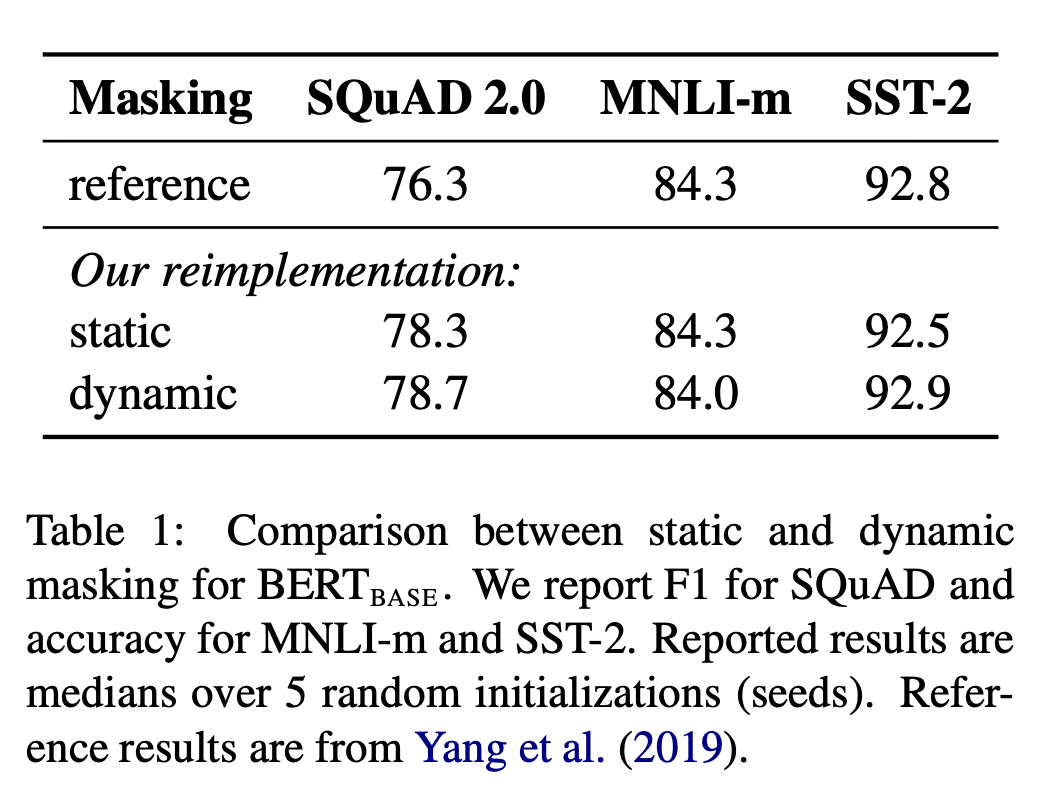

They also implement an masking strategy called dynamic masking, which randomly masks tokens throughout the training process rather than consistently masking identical token positions.

Intuitively, as most would likely concur, dynamic masking appears inherently more effective than static masking approaches. However, the empirical results indicate:

We find that our reimplementation with static masking performs similar to the original BERT model, and dynamic masking is comparable or slightly better than static masking.

:D

The followings are all approaches:

Specifically, RoBERTa is trained with dynamic masking (Section 4.1) FULL-SENTENCES without NSP loss (Section 4.2) large mini-batches (Section 4.3) a larger byte-level BPE (Section 4.4)

And they assert that BPE has advantages although it doesn't show a better performance.

Early experiments revealed only slight differences between these encodings, with the Radford et al. (2019) BPE achieving slightly worse end-task performance on some tasks. Nevertheless, we believe the advantages of a universal encoding scheme outweighs the minor degredation in performance and use this encoding in the remainder of our experiments. A more detailed comparison of these encodings is left to future work.

In abstract:

we present two parameter reduction techniques to lower memory consumption and increase the training speed of BERT (Devlin et al., 2019). Comprehensive empirical evidence shows that our proposed methods lead to models that scale much better compared to the original BERT.

I'll just introduce the methodologies of ALBERT brifely.

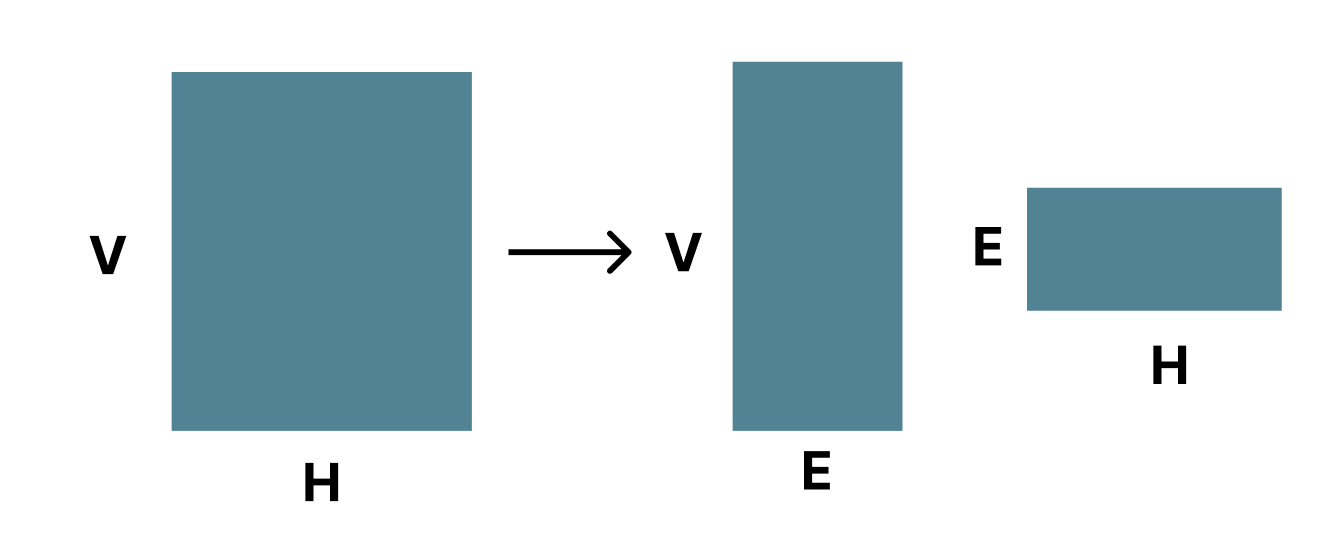

The first one is a factorized embedding parameterization. By decomposing the large vocabulary embedding matrix into two small matrices, we separate the size of the hidden layers from the size of vocabulary embedding.

The second technique is cross-layer parameter sharing. This technique prevents the parameter from growing with the depth of the network.

These approaches yield efficiency gains:

An ALBERT configuration similar to BERT-large has 18x fewer parameters and can be trained about 1.7x faster.

The first one:

Therefore, for ALBERT we use a factorization of the embedding parameters, decomposing them into two smaller matrices. Instead of projecting the one-hot vectors directly into the hidden space of size H, we first project them into a lower dimensional embedding space of size E, and then project it to the hidden space. By using this decomposition, we reduce the embedding parameters from O(V × H) to O(V × E + E × H).

The second:

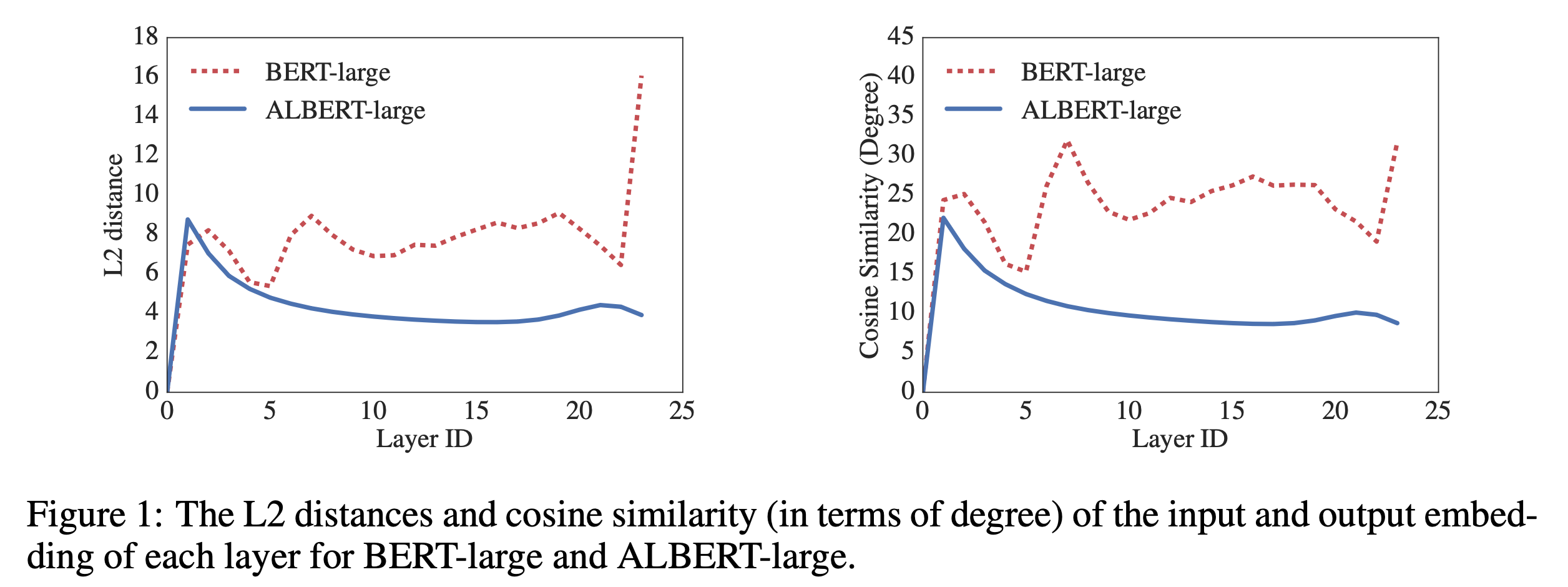

We observe that the transitions from layer to layer are much smoother for ALBERT than for BERT. These results show that weight-sharing has an effect on stabilizing network parameters. Although there is a drop for both metrics compared to BERT, they nevertheless do not converge to 0 even after 24 layers. This shows that the solution space for ALBERT parameters is very different from the one found by DQE. Although there is a drop for both metrics compared to BERT, they nevertheless do not converge to 0 even after 24 layers. This shows that the solution space for ALBERT parameters is very different from the one found by DQE.